From Static Design to Living AI-Objects

From Carlton to Nest: how presence and AI are rewriting the design of objects

1. Intro

When did I first start calling myself a “designer of technologies”?

Back in 1997, at Domus Academy. It was during a course on Interaction Design.

At that time, if you were designing a drill or a screwdriver, you were considered somehow “less gifted” than those who designed chairs. I chose a fallback path.

I grew up in a house with Plia chairs by Faber Castelli in the kitchen and a Tizio by Artemide as the lamp by my bed. It was obvious I could never match the talent of those who designed iconic chairs or lamps.

So of course I had to do something different: work with computers.

But listen to this.

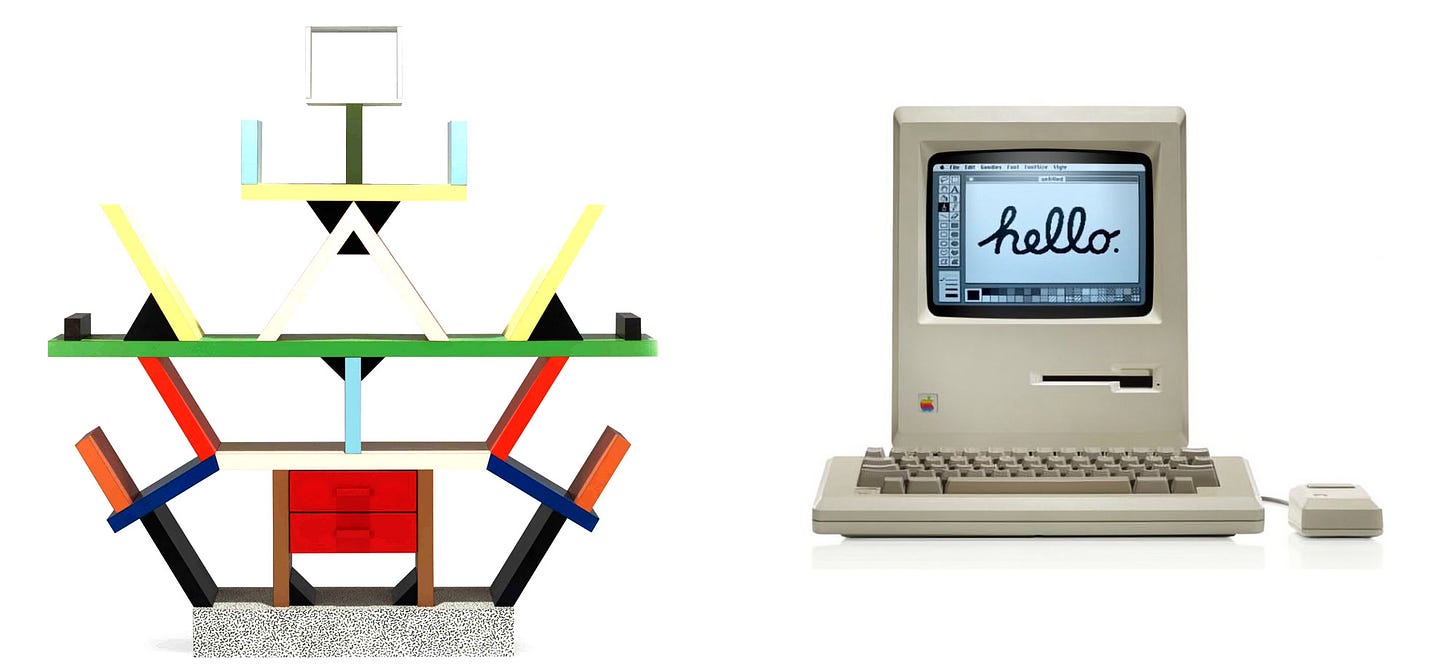

“I believe there was a precise fork in the ability of Italian Design to innovate, and that moment was the Carlton bookshelf.”

Carlton and the first Macintosh came only a few years apart. Both were born against the status quo. One was an authorial gesture, a livable sculpture. The other put power directly into people’s hands.

Today they sit in the same museum. One is an object to admire, rarely found in anyone’s home. The other conquered millions of households and fueled one of the most powerful companies on the planet.

It is the contrast between a positively egocentric vision—where the architect’s gaze alone redefines the world—and a user-centric vision, where Apple builds the tool, not the artwork.

It’s about time we reflect on that. Finally.

2. It’s always Palo Alto

From the window of my studio on Bryant Street, I can see Waverley, the parallel street. That’s where the Jobs family still lives.

Ettore Sottsass, father of the Carlton and leader of Memphis, also spent years here. Memphis took its name from a Bob Dylan verse—the same Dylan who, along with Joan Baez, obsessed Steve Jobs. Different worlds, same references, same town. Maybe it’s no coincidence that the iPod arrived before so many other things.

(btw. the picture is obviously a Nanobanana fake)

I went toward technology. Because I knew it would be technology—not lamps—that would shape the world.

First the internet. Then mobile. Then IoT. And when sensors sprouted wheels, arms, and legs, technology began to move into unthinkable places.

With AI—and with the fusion of physical and digital that robotics accelerates—I return to that boundary: lamps and chairs on one side, technologies on the other.

An object can be beautiful. Ergonomic. Iconic. But if it doesn’t know where it is and who is in front of it, it remains mute.

The real line to cross is not between lamp and robot. It’s between inert and aware.

And that’s where presence comes into play.

3. The Concept of Presence

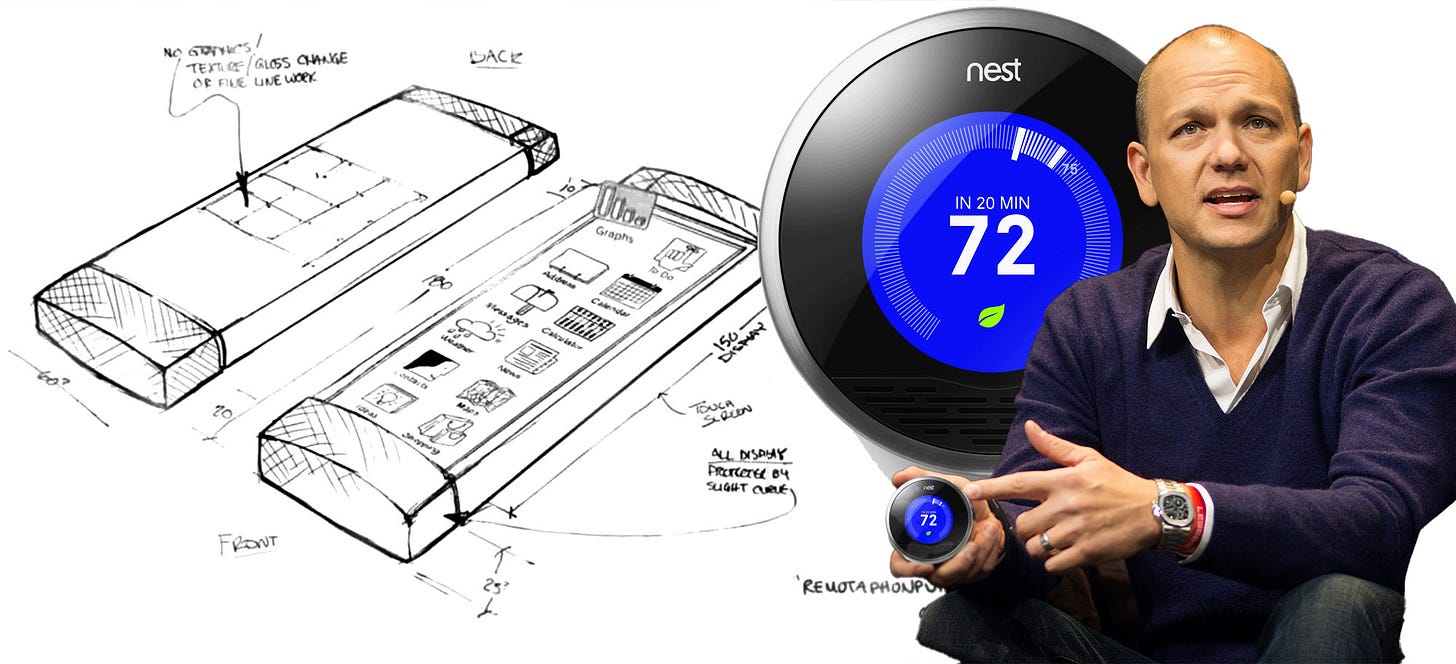

One of the first context- and presence-aware objects to enter our homes? A thermostat.

Before it became a brand, Nest was a simple idea: read the context, understand who is there and what is happening, and react. A static object that suddenly knew how to be in the room.

Google bought it for 3.2 billion dollars.

Why? Because Nest wasn’t built like a traditional thermostat.

In Italy—and especially in Brianza—you find dozens of small and mid-sized companies that have produced thermostats for decades. Their formula was always the same: an electrician, maybe an engineer, and some cousin writing the firmware. Hardware first, software as an afterthought.

Nest reversed the equation. Among the first hundred people at Nest, almost no one was focused on hardware. The center of gravity was software, experience, the digital mindset.

That’s the real innovation: doing the same thing in a radically different way. Not starting from the plastic box on the wall, but from the intelligence behind it. And that difference is what turned a thermostat into a silent assistant—and created billions in value as a side effect.

Tony Fadell had trained this vision long before: first at General Magic, then at Apple with the iPod and iPhone. Not the object or its mechanics at the center, but the experience.

When he founded Nest Labs in Palo Alto in 2010, he brought that mentality into the home. A thermostat that knows who is there, knows what to do, and acts only when necessary. You don’t command it—it (try to) collaborates.

Palo Alto is a cultural epicenter. Even if you’re just a passerby, it shapes you.

4. Calm Tech & Disappearing Computing

Thirty years ago, Mark Weiser wrote that the most powerful technology is the one that disappears.

Not hidden away, but seamlessly integrated. Present only when needed.

Calm doesn’t mean silent. It means non-intrusive.

Three principles:• Relevance — act only when needed.

• Timing — know when to speak and when to stay silent.

• Invisibility — don’t invade physical or mental space.

AI and robotics make this harder, not easier.

A machine that can move is louder by definition, even when it says nothing. The challenge is no longer adding “smart” to old appliances, but designing objects that know how to stay still.

The good examples keep the core function invisible. The bad ones add screens, apps, and notifications—dumping the filtering work on the user.

That’s the real test of calm tech: whether it brings AI and motors that can vanish into the background, or whether it turns every object into just one more noisy companion.

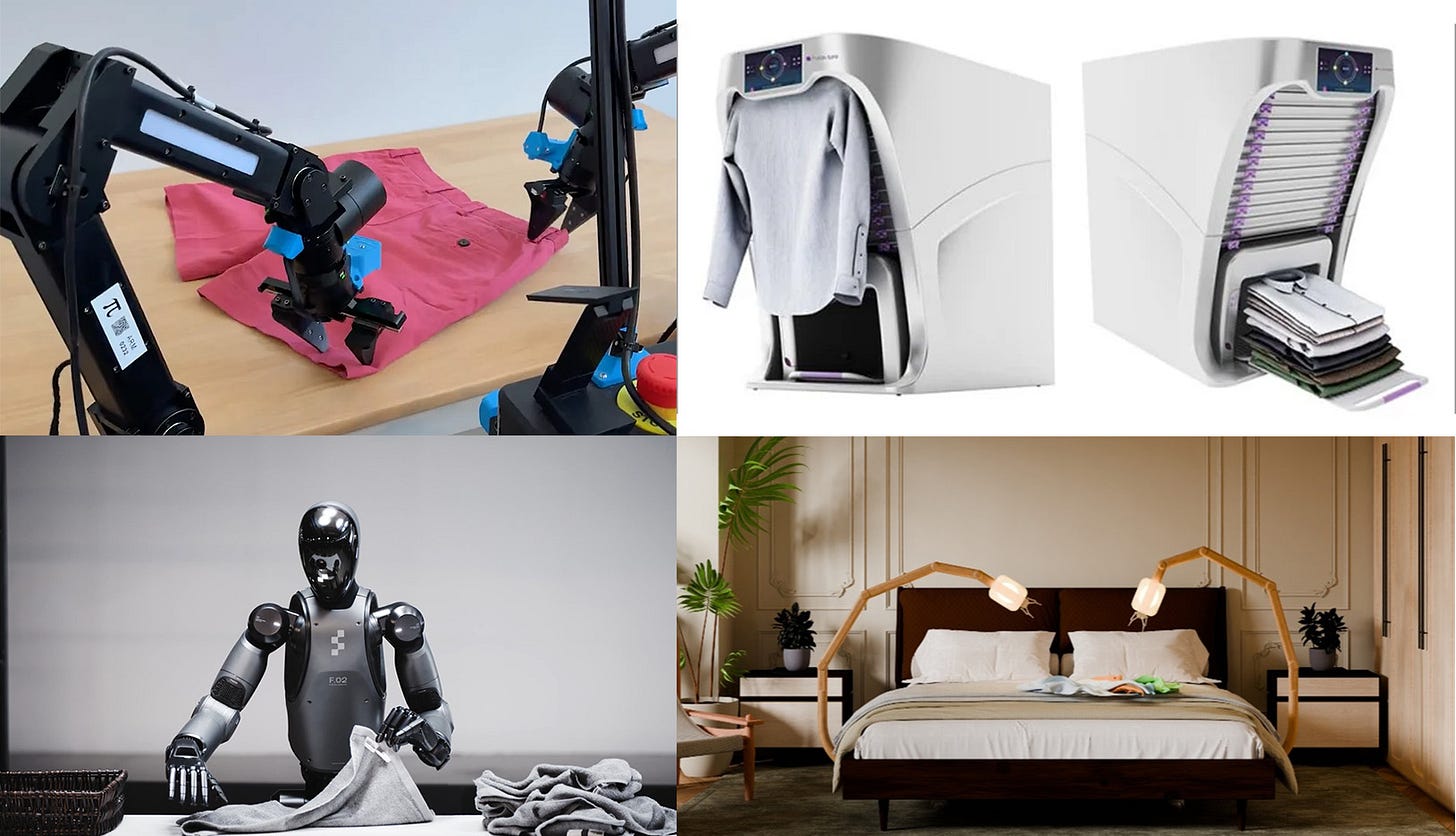

Who knows, maybe the future won’t arrive with flying cars, but with neatly folded T-shirts.

5. Let’s talk about lamps

An object that seems straight out of Beauty and the Beast, but with its feet firmly in Palo Alto: two bedside lamps that, when needed, extend robotic arms and fold your laundry.

Not all revolutions come from labs or factories. Sometimes they arrive disguised as bedside lamps. Lume, created by Stanford researcher Aaron Tan, looks like a pair of sleek, ordinary lights. Until it doesn’t. At a trigger, hidden robotic arms extend and begin folding your laundry. The video went viral in hours: millions of views for what seemed like a simple, almost magical gesture.

This is not sci-fi, and not even robotics in the traditional sense. It is ambient robotics: an object that hides in plain sight, silent and familiar, until it chooses to act. Not humanoid, not omnipotent—just a lamp that suddenly isn’t a lamp anymore.

And that’s the point. Lume lives in ambiguity. It rests inert by your bed, then reveals an intent. You can’t look it in the eye—there is no eye. No face, no signal, no feedback loop. You don’t know exactly when it will move. Calm flips into unpredictability. Presence without predictability is no longer reassuring—it is threatening.

This is exactly the fracture: not between static and dynamic objects, but between what generates presence and what generates intimacy.

Wearables live on the body and create constant intimacy. But a lamp that suddenly moves introduces presence into the space around you—and that makes it at once more powerful and more disturbing.

Cultural acceptability here is close to zero. A lamp that extends mechanical arms next to your bed is more disturbing than desirable. Viral fascination doesn’t translate into adoption. Lume will never be a mass-market product.

But its importance is not in selling units. It’s in marking a boundary: the moment when objects stop being passive furniture and start demanding a new contract with their users.

The lesson of Lume is not laundry. It is coexistence.

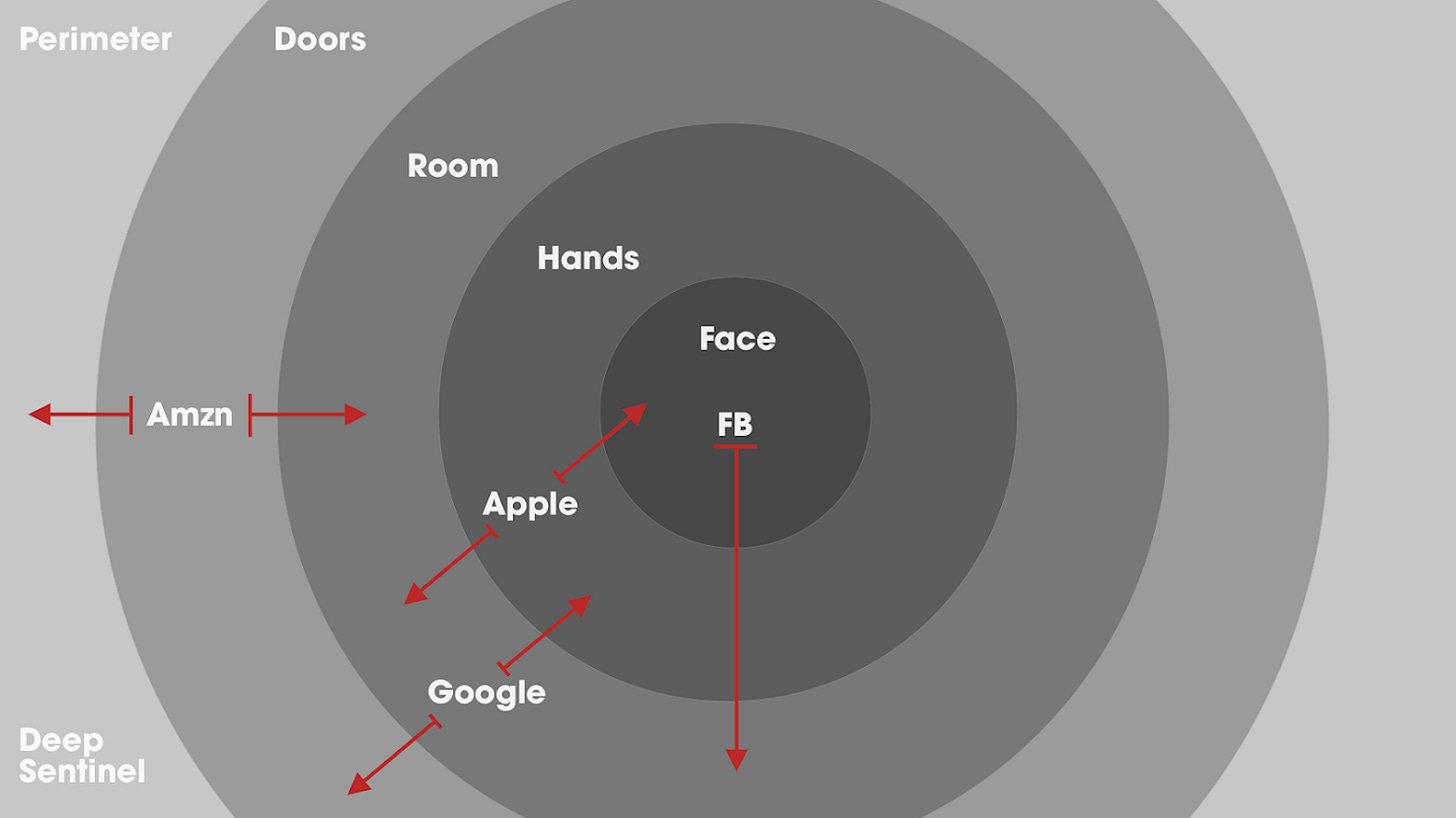

This chart comparing Apple, Meta, Google, and Amazon makes it clear: some dominate the face and hands, others the room or the perimeter. But the real tension is at the point of contact between presence and intimacy.

But if a shape-shifting technology, with arms and mechanical fingers, decides to move out of time, the only possible outcome is anxiety. Because it can touch you. And the object, which a moment before was a bedside light, suddenly becomes a foreign body in your intimacy.

6. On domestic cobots

In industrial settings, collaborative robots (cobots) introduced a strict principle: machines can share space with humans only if their presence is legible, their movements predictable, and their limits of force and speed guarantee safety.

Here, intimacy is not about proximity but about context. The worker knows what to expect; the robot operates inside procedures, with boundaries that make its behavior transparent. Predictability is trust.

Lume brings this paradigm into the domestic sphere, where intimacy is no longer about work but about daily life. A lamp that turns into a bedside cobot is not a generalist robot. It does not roam the house, it does not mimic humans. It is an object that lives in co-presence: silent, familiar, ready to act without being asked, yet capable of reshaping our sense of what feels safe at home.

Lume will never become a mass-market product. Its cultural acceptability remains low: the idea of a lamp extending mechanical arms next to your bed is more disturbing than desirable. Viral fascination stops at curiosity, rarely turning into adoption.

The true innovation of projects like Lume is not in automating chores, but in negotiating a new form of coexistence between humans and machines—in a context where presence is never neutral but always personal: the home.

⸻

7. Conclusions

The opportunity—and the responsibility—today is to integrate digital design, AI, and robotics into everyday life. Not as isolated experiments or iconic sculptures, but as silent, decisive infrastructures capable of redefining the home system—just as washing machines, refrigerators, and televisions did in the 1960s.

Presence is not a detail. It is the raw material of the new design. Physical presence isn’t neutral. And Physical AI rewrites the rules.

Design today is not about aesthetics. It is about defining a protocol of coexistence. Presence isn’t decoration. It’s power. And it always comes at a price.

PS. Recently I’ve been running a parallel experiment: a fridge-GPT, complete with a user manual and a chatbot trained on it, so I could actually converse with my refrigerator. A different angle on presence—voice, negotiation, reassurance.

What a beauty, fro DYSON: https://www.dyson.com/lighting/desk-lamps/solarcycle-morph-cd06/black-brass

https://spectrum.ieee.org/home-humanoid-robots-survey

Factories first, homes next? (Sep 2025)